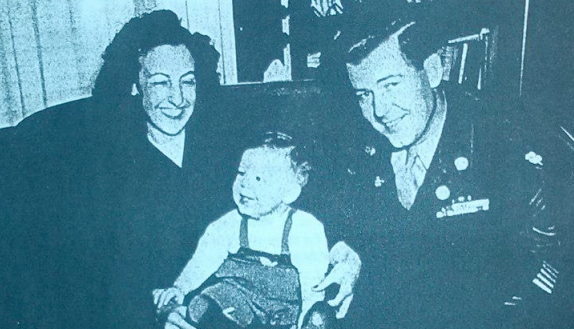

For most Americans the Korean War is long over. However, for Tennessee native Tom Forehand Jr., the war never ended. You see, his father, Army Master Sergeant Tom Forehand Sr., came up missing in April 1951 on Hill 412 which was overrun by Chinese Communist forces. Tom Jr. has spent most of his life wondering and researching about Hill 412 and the whereabouts of his father. He is now making 130 pages of his research available to his fellow military history researchers and others interested in the bloody Korean War. Look inside for an excerpt describing the battle of Hill 412 and a link to Forehand’s entire work.

NOTE: Please see Forehand’s entire research paper linked below for footnotes and credits.

Between the time Mom started writing Tuesday night and awoke to finish her letter on Wednesday morning events took place in Korea that would change our family forever.

Not long after the CCF attacked on April 22nd, our UN forces began a planned withdrawal across much of the 38th Parallel. The 7th Infantry Regiment was chosen to provide a rear guard action on the western part of the battlefield. This meant Dad’s regiment would be coming out last![196]

After two days of fighting along the 38th, Dad’s “7th” was still straddling the Uijongbu‑Seoul highway and positioned on 3rd Division’s right flank.[197] On the evening of April 24th, not long after 1st Battalion had returned from an expedition to aid part of the British Independent Brigade, spring fireworks began. Around 8 p.m. the CCF 29th Division effectively assaulted Dad’s regiment and pounded the hardest on 2nd Battalion. By 2:30 a.m., 2nd Battalion, surrounded by the enemy, was forced to break up into small units and to withdraw to the south. Yet the “1st and 3rd Battalions held their ground [while remaining] under pressure throughout the night.”[198]

Before darkness fell on April 24th, Dad and others were dug in snugly on Hill 412 positioned high above the field of battle and due south of 1st Battalion. One of those on Hill 412 was L. M., former S2 (Intelligence Officer) of 3rd Battalion. Although L. does not recall Dad, he does remember certain events that night as the observation‑post, o‑p, team was harassed by enemy fire. When the only medic took a bullet in the leg, L. says that he rushed to the aid of several of the wounded. L. administered a morphine surret to one young soldier who had taken a “slug in the chest.”

Then B. J. ‑‑ a 6’3″ American Indian I had in the section, took a fragment in the left foot. [I went] back to the [wounded medic to get] more shots for Jim and the 2nd shot for the other man….The chest wound is still screaming. I called Bn. Aide station & asked if I could give 3rd shot of morphine. The Dr. told me to hold my hand on his chest and count his breathing and if he breathed X [number of] times in a minute I could give another shot. I’m counting; we get incoming; I lose count….he might as well die comfortable. I give the third shot‑‑ then went to the medic…he rigged up a blood plasma needle and bag. And I inserted the plasma needle. He lived.[199]

By 4:00 a.m., the o‑p men were in trouble! The CCF had almost surrounded the hill.[200] Just as Dad had written, there was no such thing as a “rear echelon” in the Korean War. L. B. of L Company remembers the general situation found on many parts of the battlefield that day: the “morning…was foggy and the Chinese were everywhere‑‑in front of us, behind us and even mixed in among us.”[201] Around 7 a.m., 175 CCF attacked Hill 412 with “a sudden and strong assault.” They stormed in primarily from the west and were running with weapons held at “high port.”[202]

If the CCF could take the hill, they could rain weapons fire on top of the rear of 1st and 3rd Battalions only a few hundred yards away. To boot, from a commanding position on Hill 412, the CCF might be able to block a withdrawal by the regiment. The best route for this withdrawal was near the northern base of Dad’s hill. So, the Chinese had to take that hill; and the handful of troops we had on the hill had to get off or be captured. Being captured on top of Hill 412 was not really a liveable option. Why? The hill was so strategically located that if the Chinese controlled it, our own military would be forced to devastate the hill with air strikes (such strikes may have already been under consideration).

The team had to get off. But how? The o‑p team split into at least two different groups with one group heading north toward 1st Battalion and the other heading south off the backside of the giant hill.[203] It seems that one of the first to leave was Dad. From his position on the o‑p, he surely took off as fast as his stocky, thirty‑seven‑year‑old legs could carry him. More than once he exposed himself to enemy automatic weapon fire and grenade blasts. The CCF had attacked earlier that morning nearby hurling one pound blocks of TNT as grenades. Also some of the CCF who had attacked earlier were armed with a new type of weapon, a “38 Caliber” carrying a twenty‑round clip.[204] Yet, in spite of these obstacles and not caring for his own safety, Dad, surely dodging and weaving, made it to the crest of an adjacent hill.

How did he make it that far? Was it luck? I don’t think so. Only a few days before, Dad had written that the destiny of our nation was possessed by a force much stronger than human ability. Could this not also be true for the destiny of a small band of men as well? I think so‑‑I believe an unseen hand was helping these men.

Yet there may have been a few practical reasons why Dad made it to that nearby knoll. During his sprint, Dad seems to have been getting fire support from 1st Battalion just north of Hill 412.

Sergeant Lock, in charge of the left‑flank platoon [1st Battalion, Co. A], watched this enemy action [at Hill 412] and, as soon as he realized what had happened, turned his machine gun toward the Chinese to restrict their movement and help the members of the observation‑post party who were escaping toward the south and the north in order to rejoin Company A. Sergeant Lock also called Mooney [Lt. Harley F. Mooney commanded Company A], who immediately had his Weapons Platoon Leader [Lt. John N. Middlemas] shift his 57mm recoilless rifle to the west flank from where it could be fired more effectively against the Chinese.[205]

Another reason why Dad may have made it that far was: he was short! Since Dad was shorter than average, it would have been more difficult for an enemy soldier to frame Dad in his gun sight. Who says a guy has to be tall to be a leader of men? Dad and “Shorty” Soule stood eyeball‑to‑eyeball, chin to chin. And General Soule commanded all of 3rd Division!

At that nearby hill crest Dad had a chance to back up statements he had written earlier. He had boasted that he could shoot “pretty good” with his new rifle. Mr. J.’s family back home could vouch for that every time they remembered those rabbits Dad bagged for Mr. J. But this was war‑‑a different kind of hunting. Near Hill 412 human lives were on the line‑‑not rabbits in a pouch. And just as Dad had learned in the Great Depression, every bullet needed to count. So Dad finally had a chance to prove if what he had written was fact or fiction. Thank God what he had written was fact‑‑he could shoot! From his new position he shot well enough to cover the trailing members of his part of the o‑p team until they were finally able to reach his position.

Dad had also written that he had “a knowledge of field tactics” which “he could rely on.” But could other members of the o‑p team rely on Dad’s vintage WW II knowledge and his recently‑acquired Korean War experience? The answer soon came: Yes! Dad formed these men into a firing line. After successfully accomplishing the maneuver, he remained in place covering their flight by inflicting numerous casualties on the enemy. His actions had delayed the enemy attack and had helped his fellow soldiers to escape capture.

Apparently every member of the team had successfully gotten off Hill 412‑‑that is except for one. Just before the Lt. Colonel left the hill, he gave first aid to an injured ROK soldier. When the Lt. Colonel finally took off, he thought to himself “that’ll be the last I’ll ever see of him.”[206]

By 8 a.m., the Chinese were in “full possession” of Hill 412; and by 9 a.m. there “were still heavy exchanges of fire between the Chinese on [Hill 412]…and Lock’s left‑flank platoon.” Between 10 a.m., and 11 a.m., “four planes made a strike with napalm and rockets on the [Hill 412] causing a sudden drop in enemy fire from that area.”[207] Two hours later the regiment had been able to successfully withdraw from the area.

Their withdrawal from the 38th Parallel had gone according to plan‑‑though it had taken longer than anticipated. At one point while they were attempting to pull out, one GI, on the extreme right flank of 1st Battalion, panicked and prematurely ran from his rear‑guard blocking position. He came hurriedly shouting: “They’re coming! They’re coming! Millions of them! They’ll banzai us!” However, due to the quick thinking and action of Lt. John Middlemas, the panic was halted. Before long with the help of additional men, automatic weapons and artillery, an orderly withdrawal resumed until it was completed.[208] According to Blair:

In this action, Weyand’s A Company, commanded by Harley F. Mooney, and B Company, commanded by Ray W. Blandin, Jr., staged one of the most gallant fights of the war. An A Company corporal John Essebagger, Jr., mortally wounded, won the Medal of Honor for his “one‑man” stand and for charging the CCF, “firing his weapon and hurling grenades.” Another mortally wounded corporal in B Company, Clair Goodblood also won the Medal for heroically remaining at his post and killing 100 of the enemy before he died. The weapons platoon leader, Lieutenant John N. Middlema[s], won a DSC.

Because of the extraordinary courage of these men and others in the 1/7, both battalions completed the withdrawal without disaster. The 7th Infantry consolidated farther south and continued to provide rear guard protection for the withdrawing 3d Division elements. For extracting the Belgians on April 23 and 24 and for the “magnificent” rear guard action on April 25, Fred Weyand’s 1/7 [1st Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment] (plus attached units) was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, which credited the battalion with killing “over 3,000 enemy troops” and wounding “an estimated 5,500.”[209]

Only 78 Medals of Honor were awarded by Congress to Army personnel during the Korean War‑‑two of them were awarded to men on the ridge line directly below Dad’s Hill 412. The fighting was so furious and gallant throughout the entire 7th Infantry Regiment front that another Medal of Honor was earned early that morning by Corporal Hiroshi Miyamura of 2nd Battalion.[210] Later, Dad would be awarded the Silver Star for “extreme gallantry and complete devotion to duty” in helping men to escape from Hill 412. First Battalion Commander Lt. Colonel Weyand would eventually become a four‑star General and serve as army chief of staff.[211]

By the end of the day most of our UN forces were quickly withdrawing southward toward a perimeter surrounding Seoul.[212] E.S, blessed to have been in Seoul when the attack of April 25th took place, remembers that the “Chinese attack went on for 5 days, pushed us back over 20 miles to south of Uijonbu before we stopped them….”[213] The Communists were never able to break through our UN barrier around Seoul and would never enter Seoul again. Within a few weeks our forces came out of their defensive corner swinging and punching the CCF all the way back above the 38th Parallel again.